(With apologies to Paul Rodgers)

57M in US Still Acquiring Unlicensed Music

The BBC reported on February 17 that Kanye West’s “Life of Pablo” has already been pirated 500,000 times. According to the article on The Next Web quoting those statistics, piracy is at historic lows. Respectfully, that is a popular belief, though wholly incorrect. The rationale goes like this: Education and judicial action have reformed the majority of consumers. The shift to digital downloads made ripping and burning CDs obsolete. The emergence of legal streaming and smartphones means that “pirates” now listen to Spotify and Pandora. With only a few remaining hardcore miscreants, the high seas have mostly been cleansed of pirates—and we can declare Mission Accomplished.

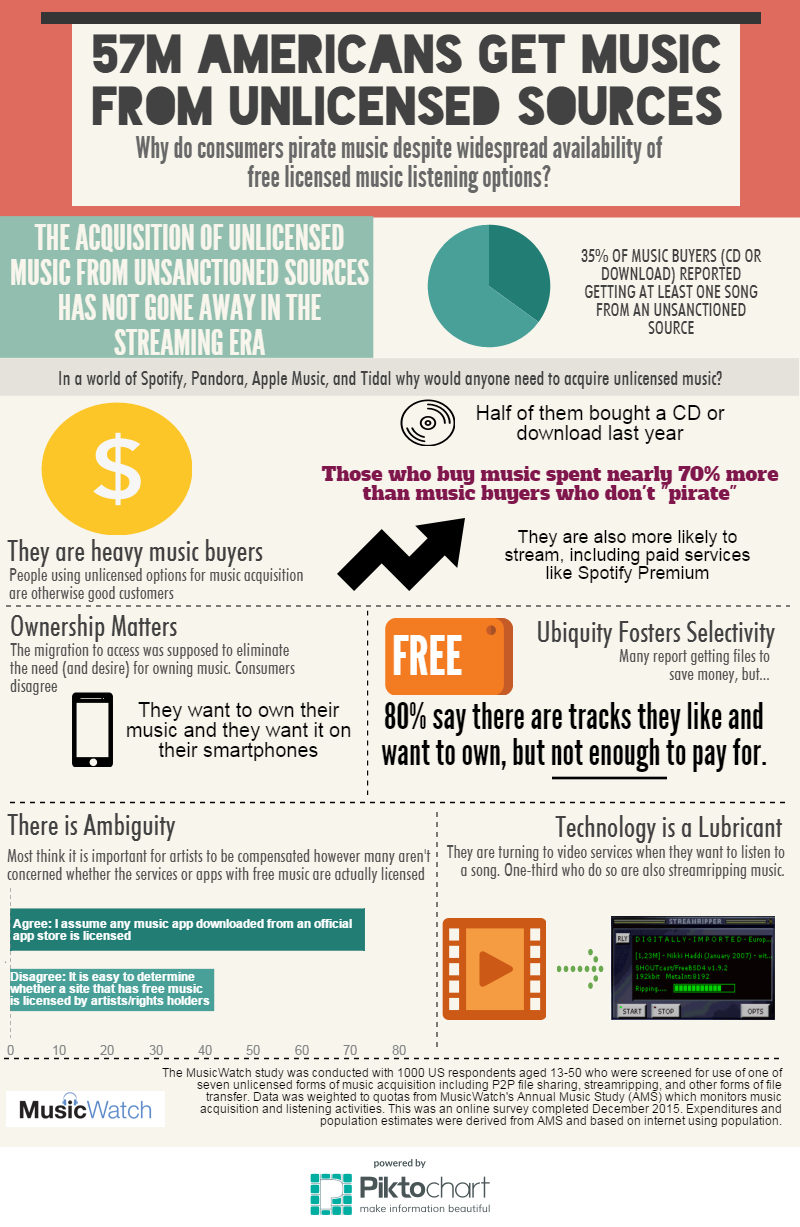

This is an entirely incorrect proclamation. Acquisition of unlicensed music from unsanctioned sources has not gone away. How bad is it? In 2004 we estimated there were 41M folks in the US illegally downloading music from P2P networks at a time when many weren’t even regular users of the internet. Last year that number dwindled to 22M, with the number of files being downloaded also in decline. However, now there are more forms of unlicensed acquisition available than in 2004; streamripping, downloading from storage lockers, mobile apps, and hard drive swaps.

In all forms, we estimate 57M Americans are engaging in these forms of music acquisition. We call it “badquisition:” acquiring music from bad or unlicensed sources. Another startling statistic: 35% of music buyers (CD or download) also reported getting at least one song from an unsanctioned source. This is not exclusively a problem among people unwilling to pay for music.

We call the participants who get music from these sources “badquirers”. The question is, in a world of iTunes, Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, Tidal or Deezer, why would anyone need to participate in “badquisition” of music? We set to find out, and here’s what we learned from a recent study:

- Ownership Matters. The migration to access was supposed to eliminate the need (and desire) for owning music. Consumers disagree. Research shows “badquirers” want to own the music. They also want it available on their smartphones. Some express concerns about data usage but ownership is a higher priority. This is not surprising as our other studies point to continued perceived value in possessing a song or album.

- Ubiquity Fosters Selectivity. As expected, many “badquirers” report getting files because they are free, or at least cheaper. But it is more complicated than that— there are tracks they like and want to own, but not enough to pay for. Streamripping, mobile download apps and P2P provide an avenue for obtaining those files and permit listeners to be more selective in what they buy.

- Technology is a Lubricant. “Badquirers” often turn to video services when they want to listen to a song. One-third of those who do so are also streamripping music. They often do an internet search for the song or artist which, coincidentally, is the leading way they learn about unsanctioned sources for music. Speaking of streamripping, we estimated a 50% increase in the number of streamrippers in the US between the end of 2013 and early 2015. There are nearly as many streamrippers in the US as folks who illegally download music files from P2P networks.

- There is Ambiguity. 73% of “badquirers” agreed with this statement; “I assume any music app that I can download from an official app store is licensed by artists and rights holders.” 58% said it was easy to determine whether a site that has free music is licensed by artists and rights holders—42% disagreed.

- Communication Breakdown? “Badquirers” are getting music that they believe is officially released, but is not available on streaming services or they can’t find it on CDs or downloads. And yes, they also look for remixes and bootlegs unlikely to be found on licensed services. Are consumers well informed on what is available on streaming services? Does more need to be done with pre-release alerts? Or is there indeed a gap in catalogs?

- They are Heavier Music Buyers. People using unlicensed options for music acquisition are otherwise good customers, spending $33 per capita on CDs and paid digital downloads. The US average is $19 per capita. Half of them bought a CD or download last year, which is a higher percentage than the population as a whole. They are also more likely to stream, including using paid services such as Spotify Premium. However, the $33 per capita is less than the $45 expenditure of the average music buyer.

The study did not measure the economic impact of these activities. It is fair to speculate that revenues are being siphoned from artists. These people are more likely to buy music and they value ownership of music—yet they can be more selective as a result of mobile apps, streamripping and P2P. Not every rip or download would translate to a sale but certainly some would.

Much success has been made thwarting P2P usage. Unfortunately other sources for unlicensed music now boast millions of users. For those who participate it raises a number of questions: Why pay for premium on-demand streaming when I can get on-demand elsewhere? How impermeable are pay-walls, exclusives and windows when consumers can readily circumvent them? It’s not exclusively a music problem—if they’re doing it for music they’re likely doing it for TV shows, movies and games as well. It’s time to reset our thinking about music piracy.

The MusicWatch “Badquisition” study was conducted among 1000 US respondents aged 13-50 who were screened for use of one of seven unlicensed forms of music acquisition including P2P file sharing, streamripping, mobile apps and other forms of file transfer. The data was weighted to quotas from MusicWatch’s Annual Music Study (AMS) which monitors music acquisition and listening activities. This was an online survey completed December 2015. Expenditures and population estimates were derived from AMS and based on internet using population aged 13 and older.